Introduction - What is the Research Onion & Why Does it Matter?

The Big Picture: What is Research Design? (Your Research Blueprint)

Imagine you decide to build your dream house. Would you just start laying bricks randomly, hoping it ends up standing? Of course not! You'd start with a blueprint. This detailed plan would show the foundation, walls, rooms, plumbing, electrical wiring, and roof – all working together to create a safe, functional, and beautiful home. Without that blueprint, you'd face chaos, wasted resources, and likely a collapsed structure.

Research Design is the blueprint for your dissertation.

Think of your research project as building that house. Your research question is the purpose of the house (e.g., "a family home," "a modern office"). Your research design is the comprehensive plan outlining how you will construct the knowledge to answer that question. It’s the master strategy that guides every single step you take, ensuring your investigation is rigorous, coherent, and eventually capable of producing valid and reliable answers.

A good research design doesn't just list what you'll do; it explains why you'll do it that way. It considers:

What you need to find out (your research questions/objectives).

Why it's important to find this out (the research gap and significance).

How you will go about finding it out (the methods, data, analysis).

Who or What you will study (your sample or case).

Where and When you will conduct the study (context and time frame).

Why this specific approach is the best way to answer your question (justification).

Without a solid research design, your dissertation risks becoming a collection of disconnected activities, leading to confusion, wasted effort, and conclusions that lack credibility. Just like the house blueprint, your research design is the essential foundation upon which everything else is built.

Introducing the Research Onion: Your Visual Guide to Research Design

So, where does the "Research Onion" come in? It's one of the most popular and user-friendly models for understanding and structuring research design, especially in business, social sciences, and many other fields.

Who Created It? The Research Onion model was developed by Mark Saunders, Philip Lewis, and Adrian Thornhill, prominent researchers in the field of business and management research. They introduced it in their highly influential book, "Research Methods for Business Students" (first published in 1997, now in its 8th edition). It's become a staple in methodology courses worldwide because of its clarity and practicality.

What Does It Look Like? Imagine a large onion. Now, picture it sliced in half, revealing its concentric layers. The Research Onion looks exactly like this:

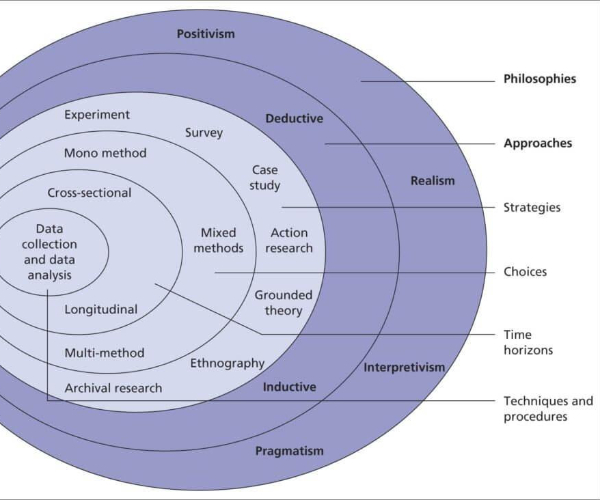

Figure 1 Research Onion Framework

Outermost Layer (Ring 1): Research Philosophy

Layer 2: Research Approach

Layer 3: Research Strategy

Layer 4: Research Choice

Layer 5: Time Horizon

Innermost Core (Ring 6): Techniques and Procedures

Each ring represents a crucial decision point in designing your research. The model visually emphasizes that these layers are interconnected and build upon each other. You start making decisions at the outer layer and work your way inwards, like peeling an onion layer by layer to reach the core. The choices you make in the outer layers fundamentally shape and constrain the choices available to you in the inner layers. It's a holistic, visual roadmap for navigating the complex terrain of research design.

Why Use the Onion? Benefits for YOUR Dissertation

Okay, the onion is a nice picture, but why should you, a novice student grapple with your dissertation, bother with it? Because using the Research Onion framework offers concrete, practical benefits that directly address common student struggles and significantly boost your chances of dissertation success:

Provides a Systematic Way to Plan Your Research:

The Problem: Starting a dissertation can feel overwhelming. Where do you even begin? What decisions need to be made first?

The Onion Solution: It gives you a clear, step-by-step sequence. You know you must start by considering your Research Philosophy (Layer 1) before you can logically decide on your Approach (Layer 2), and so on, moving inwards. It prevents you from jumping straight to "I'll do some interviews!" without considering why interviews are appropriate or what philosophical stance underpins that choice. It transforms an intimidating task into a manageable, logical process.

Ensures All Crucial Methodological Decisions Are Considered:

The Problem: It's easy to forget important aspects of research design, especially when you're new to this. You might focus heavily on data collection (interviews, surveys) but neglect to explicitly state your underlying philosophy or justify your chosen approach.

The Onion Solution: The model acts as a comprehensive checklist. Each layer represents a critical component of a robust research design. By systematically working through each layer, you are forced to confront and make a conscious decision about every major aspect: your beliefs about knowledge (Philosophy), your reasoning path (Approach), your overall plan (Strategy), your data type (Choice), your timeframe (Time Horizon), and your specific tools (Techniques). Nothing vital gets overlooked.

Helps Justify Your Choices to Your Supervisor/Examiners:

The Problem: One of the biggest challenges in writing a methodology chapter is justifying your choices. Why did you choose interviews over a survey? Why a case study instead of an experiment? Examiners don't just want to know what you did; they want to know why it was the most appropriate way to answer your specific research question. "It seemed easier" or "I read about it" won't cut it!

The Onion Solution: The framework provides the structure for your justification. Because the layers are interconnected, your justification naturally flows: "Given my [Research Philosophy - Layer 1], which emphasizes understanding subjective meanings, the most logical [Research Approach - Layer 2] is Inductive. This Inductive approach is best implemented through a [Research Strategy - Layer 3] like a Case Study, allowing for deep exploration. This strategy necessitates a [Research Choice - Layer 4] of Qualitative data, collected via [Techniques - Layer 6] such as interviews, analyzed thematically." Each choice is explicitly linked to and justified by the layer outside it and, ultimately, your research question. This demonstrates rigorous thinking. Further, observations can be of two types based on time horizons, namely cross-sectional and l

Makes Your Methodology Chapter Organized and Logical:

The Problem: A methodology chapter can easily become a messy, disjointed narrative if you're not careful. Jumping between topics makes it hard for your reader (and you!) to follow your reasoning.

The Onion Solution: The layers provide a ready-made, logical structure for writing your chapter. You can literally structure your methodology section by following the onion layers: start with Philosophy, then Approach, then Strategy, and so on, ending with Data Collection and Analysis. This creates a clear, coherent narrative that guides your reader systematically through your research design decisions, making it easy to understand and evaluate. It shows you have a well-thought-out plan.

In short, the Research Onion isn't just a theoretical model; it's a practical toolkit that brings order to chaos, ensures completeness, provides the language for justification, and structures your writing. It empowers you to design and defend your dissertation research with confidence.

The Core Idea: Peeling the Layers - The Journey from Broad Assumptions to Specific Techniques

The fundamental genius of the Research Onion lies in its core metaphor: Peeling the Layers. This represents the essential journey you take when designing your research, moving from the broad, abstract foundations to the concrete, practical details.

Starting Broad: The Outer Layers (Philosophy & Approach): The outer layers deal with the big ideas and fundamental assumptions.

Research Philosophy (Layer 1): This is the absolute core of your research worldview. It forces you to ask deep questions: "What is the nature of reality?" (Ontology) and "What constitutes valid knowledge?" (Epistemology). Are you seeking one objective truth, or are you exploring multiple socially constructed realities? Is knowledge best gained through measurement and observation, or through interpretation and understanding? These are broad, often philosophical, stances that underpin everything you do. They are the bedrock.

Research Approach (Layer 2): Building on your philosophy, this layer defines the overall path or logic you will take. Will you start with a theory and test it (Deductive)? Or will you start with observations and build towards a theory (Inductive)? Or will you focus on finding the most practical solution to a problem (Abductive)? This layer dictates the fundamental reasoning process you'll use.

Moving Inwards: The Middle Layers (Strategy, Choice, Time Horizon): These layers translate your broad philosophy and approach into a more concrete plan.

Research Strategy (Layer 3): This is your master plan. How will you implement your chosen approach? Will you conduct an experiment? A survey? An in-depth case study? An ethnography? This layer defines the overarching framework for your data collection and analysis.

Research Choice (Layer 4): Here you decide on the fundamental nature of the data you need. Will it be primarily numbers and statistics (Quantitative)? Words, descriptions, and meanings (Qualitative)? Or a combination of both (Mixed-Methods)? This choice is heavily influenced by your Strategy and Approach.

Time Horizon (Layer 5): This layer addresses the dimension of time. Will you take a snapshot at one point in time (Cross-Sectional)? Or will you study your subject over a period of time to observe change or development (Longitudinal)? This practical consideration shapes your data collection schedule.

Reaching the Core: The Innermost Layer (Techniques): After establishing your foundational beliefs, reasoning path, overall plan, data type, and timeframe, you finally specify the exact tools you will use.

Data Collection Techniques: Precisely how will you gather your data? Will you conduct semi-structured interviews? Distribute online questionnaires? Observe behaviour in a setting? Analyse company documents? Run specific experiments?

Data Analysis Techniques: Exactly how will you make sense of the data you collect? Will you use statistical tests (like t-tests or regression)? Will you perform thematic analysis to identify patterns in interview transcripts? Will you use discourse analysis? These are the specific, hands-on methods.

The Journey Summarized: Peeling the Research Onion means starting with your deepest beliefs about knowledge (Philosophy) and the logical path you'll take (Approach). You then use these to choose your overall research plan (Strategy), decide on the type of data you need (Choice), determine the timeframe (Time Horizon), and finally, select the specific tools to gather (Data Collection) and interpret (Data Analysis) that data. Each layer informs and constrains the next, ensuring your entire research design is a coherent, justified whole, perfectly tailored to answer your unique research question. It's a journey from abstract thought to concrete action.

Layer 1: Research Philosophy (The Outer Core - "What is the Nature of Reality & Knowledge?")

What It Is: The Core of Your Research

Research Philosophy is the deepest layer of the Research Onion, representing your fundamental beliefs about two critical things:

Ontology: What is the nature of the reality you are studying? Does it exist independently of human consciousness, or is it created by human minds?

Epistemology: What constitutes valid and legitimate knowledge about that reality? How can we know what we claim to know?

Think of it as the operating system of your entire research project. It’s not about what you study, but how you believe knowledge itself works in the context of your topic. Before you decide how to research (approach, methods), you must first confront what you believe about the world you’re researching and how we can understand it. This layer sets the rules for everything that follows.

Why It Matters First: The Foundation of Coherence

You MUST start here. Why? Because your Research Philosophy directly determines how you believe knowledge can be gained, which in turn dictates every single subsequent choice in the Research Onion:

It shapes your Research Approach (e.g., Do you test theories or build them from data?).

It guides your Research Strategy (e.g., Is an experiment appropriate, or is an in-depth study needed?).

It influences your Methodological Choice (e.g., Should you focus on numbers, words, or both?).

It underpins your Data Collection & Analysis Techniques (e.g., Should you measure variables statistically or explore meanings thematically?).

Skipping this layer or choosing a philosophy arbitrarily is like building a house on sand. Your methodology becomes a collection of disconnected techniques rather than a coherent, justified system. Starting with philosophy ensures every layer of your research design aligns logically, creating a robust and defensible dissertation.

Key Philosophies Explained Simply: Your Worldview Options

Here are the five major research philosophies within the Saunders framework

Philosophy | Definition | Aim | Dissertation Research Example |

Positivism | The social world has objective, measurable patterns that follow universal laws, similar to natural sciences. | Discover universal laws and cause-effect relationships. | Machine Learning: Testing whether a specific algorithm consistently predicts customer churn better than random chance, using measurable accuracy metrics. |

Realism | An objective reality exists, but we can only access it imperfectly through our senses and interpretations. | Understand hidden structures/causes despite limited human perception. | Nursing: Investigating how hospital noise levels (observable factor) affect patient recovery (underlying biological process), acknowledging individual variations in pain perception. |

Interpretivism | Reality is constructed through human experiences and social interactions. Multiple valid realities exist. | Explore diverse perspectives and lived experiences. | Cybersecurity: Examining how different employees in a bank interpret security protocols, revealing varied "realities" of daily security practices. |

Pragmatism | The best approach is whatever works to solve the research problem, regardless of philosophical purity. Often combines methods. | Solve practical problems with actionable solutions. | Public Health: Combining infection rate statistics (quantitative) with patient interviews (qualitative) to determine the most effective vaccination strategy during an outbreak. |

Postmodernism | Questions objective truths, emphasizing how language, power, and discourse shape what we accept as "reality." | Deconstruct dominant narratives and expose power dynamics. | Social Media: Analysing how beauty influencers on Instagram use specific language and visual techniques to construct "ideal" beauty standards, revealing how these narratives shape young people's self-perception and reinforce industry power structures. |

How to Choose: Finding Your Philosophical Fit

Choosing a philosophy isn't about picking your "favourite." It's about finding the worldview that best aligns with your research question and the nature of your topic. Ask yourself these critical questions:

"What is the fundamental nature of what I'm studying?"

Is it a phenomenon with clear, measurable components that behave consistently (e.g., sales figures, chemical reactions, machine efficiency)? → Positivism/Realism might fit.

Is it about human experiences, beliefs, cultures, or social interactions where meaning is subjective (e.g., employee motivation, cultural identity, customer perceptions)? → Interpretivism is likely.

Is it about complex systems where you suspect hidden structures drive surface events (e.g., market crashes, organizational failures)? → Realism could be suitable.

"What is my primary goal?"

To test an existing theory and establish cause-and-effect? → Positivism is the traditional home.

To explore a new area, understand deep meanings, or give voice to experiences? → Interpretivism provides the framework.

To solve a pressing practical problem in the real world, using whatever methods work best? → Pragmatism is your ally.

To challenge established ideas, expose power imbalances, or show how "truth" is created? → Postmodernism offers the tools.

"Link it DIRECTLY to your Research Question!"

Example Question 1: "What is the impact of social media marketing spend (X) on quarterly sales revenue (Y) in UK retail companies?"

Nature: Measurable variables (spend, sales), seeking cause-effect.

Goal: Test a relationship.

Likely Fit: Positivism (or sometimes Realism).

Example Question 2: "How do remote workers construct meaning and maintain a sense of professional identity in the absence of physical office interactions?"

Nature: Subjective experiences, social construction of meaning.

Goal: Explore lived experiences and interpretations.

Likely Fit: Interpretivism.

Example Question 3: "What is the most effective combination of training methods (A, B, C) to reduce errors in a specific hospital department, and why?"

Nature: Practical problem, need a workable solution.

Goal: Solve a real-world problem effectively.

Likely Fit: Pragmatism.

Example Question 4: "How do dominant corporate sustainability narratives in annual reports serve to legitimize or obscure environmental impacts?"

Nature: Language, power, discourse shaping "reality."

Goal: Deconstruct narratives, expose power dynamics.

Likely Fit: Postmodernism.

Crucial Advice:

Don't Panic: It's normal to find this layer challenging. Take time to reflect.

Read Around: Look at methodologies in published studies similar to yours. What philosophy do they state?

Discuss with Supervisor: This is a key conversation to have early on.

Be Prepared to Justify: You'll need to clearly articulate why your chosen philosophy is the most appropriate foundation for your specific research in your methodology chapter.

By consciously choosing and articulating your Research Philosophy, you lay the essential groundwork for a coherent, rigorous, and defensible dissertation. It’s the first, most critical "peel" of the Research Onion.

Layer 2: Research Approach (The "Path" - "How Will I Reason About the Data?")

What It Is: Your Reasoning Roadmap

Research Approach is the logical pathway that connects your Research Philosophy (your beliefs about reality and knowledge) to your actual research methods. It defines the process of reasoning you will use to move from your initial ideas to your final conclusions. Think of it as the navigation system for your research journey: it doesn't dictate the exact roads (methods), but it determines the direction and sequence of your intellectual travel. Will you start broad and narrow down? Or start with specifics and build up? Or follow clues to solve a puzzle? Your approach sets this fundamental pattern.

Why It Matters: Translating Beliefs into Action

Your Research Philosophy tells you what kind of knowledge is possible (e.g., objective facts vs. subjective meanings). Your Research Approach tells you how to logically pursue that knowledge. It matters because:

It Bridges Philosophy and Practice: It translates abstract philosophical beliefs (e.g., "I believe in objective cause-effect" from Positivism) into a concrete plan for how you'll actually reason with data (e.g., "I'll test a specific hypothesis").

It Dictates the Flow of Your Research: It determines the structure of your investigation. Do you start with theory and test it? Or start with data and generate theory? This shapes everything from your literature review focus to your data analysis plan.

It Ensures Coherence: Choosing an approach that logically flows from your philosophy is critical. A mismatch creates a flawed foundation. For example, using a Deductive approach (testing theories) with a strong Interpretivist philosophy (focusing on subjective meanings) creates tension. The approach must implement the philosophy.

It Guides Your Strategy Choice: Your approach directly influences which Research Strategy (Layer 3) is appropriate. Testing a hypothesis (Deductive) naturally leans towards experiments or surveys. Building theory from data (Inductive) leans towards case studies or ethnography.

Key Approaches Explained: Your Reasoning Options

Here are the three core research approaches, detailing their logic, flow, and philosophical links:

Approach | Logic & Flow | Key Question Driving It | Philosophy Link | Analogy |

Deductive | Theory → Hypothesis → Observation → Confirmation(Starts broad/general, moves to specific) | "Does this specific evidence support the general theory?" | Positivism/Realism (Seeks objective truth, cause-effect) | Business Research: Starts with the theory that employee training increases productivity (general), then collects specific data (pre- and post-training performance metrics) to test the theory. |

Inductive | Observation → Pattern → Tentative Hypothesis → Theory(Starts specific, moves to broad/general) | "What broader theory or pattern emerges from these specific observations?" | Interpretivism (Focuses on subjective meaning, social construction) | Education Research: Observes specific classroom interactions (student behaviors, teacher responses), identifies patterns, and develops a new theory about collaborative learning dynamics. |

Abductive | Surprising Observation → Best Explanation → Testable Hypothesis(Starts with a puzzle, seeks the most plausible explanation) | "What is the simplest, most likely explanation for this unexpected finding?" | Pragmatism/Realism (Focuses on practical solutions, underlying causes despite imperfect access) | Healthcare Research: Notices an unexpected pattern in patient recovery data (some patients recover faster than expected despite similar conditions), proposes that social support networks are the key factor (best explanation), and designs a study to test this hypothesis. |

How to Choose: Finding Your Reasoning Path

Choosing your approach isn't just about preference; it's about finding the logical path that best serves your research question and aligns with your chosen Philosophy. Ask yourself these key questions:

"What is the fundamental nature of my research question?"

Example: "Does Theory X predict customer loyalty in online grocery shopping?"

Likely Fit: Deductive. You start with Theory X, develop hypotheses (e.g., "Higher perceived ease of use will increase loyalty"), and test them with data.

Example: "How do gig economy workers in developing countries navigate job insecurity and build resilience?"

Likely Fit: Inductive. You start with specific observations (interviews, field notes), identify patterns in experiences, and gradually build a new theory about resilience strategies.

Example: "Why did our well-designed employee wellness program unexpectedly increase reported stress levels?" or "What combination of interventions could most effectively reduce student dropout rates in underfunded schools?"

Likely Fit: Abductive. You start with the surprising outcome (increased stress, dropout rates), seek the most plausible explanation(s) (e.g., program added workload, stigma around participation), and then test that explanation.

Does it start with an existing theory or model that needs testing?

Is it exploring a new or poorly understood area where no clear theory exists?

Does it involve a puzzle, anomaly, or complex real-world problem needing a practical solution?

"What is my primary goal?"

To test, verify, or apply an existing theory? → Deductive.

To explore, describe, or generate new theory? → Inductive.

To solve a practical problem or find the best explanation for something unexpected? → Abductive.

"CRUCIALLY: Does this approach logically follow from my chosen Philosophy?"

Deductive & Positivism/Realism: This is the classic pairing. Positivism's belief in an objective reality governed by laws makes testing specific hypotheses derived from theory a natural fit. Realism's focus on underlying structures also aligns with testing explanations.

Inductive & Interpretivism: This is the natural pairing. Interpretivism's focus on socially constructed meanings and multiple realities requires starting with the specific experiences and perspectives of individuals to build understanding. You can't test a pre-existing theory about subjective meaning; you need to discover it from the data.

Abductive & Pragmatism/Realism: Pragmatism's focus on solving the problem at hand makes abductive reasoning ideal – find the explanation that works best to solve the puzzle. Realism's acceptance that we perceive reality imperfectly also fits abductive reasoning, where we seek the best explanation we can derive from potentially incomplete data.

Practical Tip: Look at the literature in your field. Studies similar to yours often reveal common approaches. If most research on your topic tests theories (Deductive), ask if your question truly fits that mold, or if you're genuinely exploring new ground (Inductive). If you're tackling a unique practical problem, Abductive might be your best bet.

Remember: Your Research Approach is the critical link between your worldview (Philosophy) and your action plan (Strategy). Choosing the right path ensures your reasoning is sound, your methods are appropriate, and your entire research design hangs together coherently. It's the second essential "peel" of the Research Onion.

Layer 3: Research Strategy (The "Blueprint" - "What's the Overall Plan for Data Collection & Analysis?")

What It Is: Your Master Plan

Research Strategy is the detailed blueprint that translates your chosen Research Approach into a concrete plan of action. It specifies what type of study you will conduct to answer your research question. If your Approach is the "path" (Layer 2), your Strategy is the map that marks the terrain, landmarks, and routes you’ll take on that path. It defines the overall framework for how you will gather, analyse, and interpret data, setting the stage for the specific techniques (Layer 6) you’ll use later.

Why It Matters: The Framework That Guides Everything

Your Research Strategy is the operational heart of your dissertation design. It matters because:

It Implements Your Approach: It takes the abstract reasoning of your Approach (Deductive/Inductive/Abductive) and turns it into a tangible research design. A Deductive approach needs a strategy that allows testing (e.g., Experiment), while an Inductive approach needs one that allows exploration (e.g., Ethnography).

It Determines Your Methods: Your Strategy directly dictates which Data Collection and Analysis Techniques (Layer 6) are appropriate and feasible. You can’t conduct an Experiment without controlled observation and measurement, or an Ethnography without immersive fieldwork.

It Defines Scope and Depth: It sets boundaries for your research. Will you study one instance deeply (Case Study), many instances broadly (Survey), or a process over time (Grounded Theory)? This shapes your sample, data volume, and analysis complexity.

It Ensures Feasibility: Choosing a realistic strategy is critical. An Experiment might be ideal for cause-effect, but impossible if you can’t manipulate variables. A Longitudinal study might be perfect for tracking change, but impractical within a 6-month dissertation timeline. Strategy forces you to confront practical constraints.

It Provides Coherence: A well-chosen Strategy ensures all subsequent methodological choices (Layer 4-6) align logically with your Approach and Philosophy.

Key Strategies Explained: Your Blueprint Options

Here are the seven core research strategies, detailing their purpose, process, and links to approaches:

Strategy | Core Purpose & Process | Best For | Approach Link | Analogy |

Experiment | Manipulate & Measure: Deliberately change one variable (Independent) to observe its effect on another (Dependent) under controlled conditions. | Establishing cause-and-effect relationships with high confidence. | Deductive (Tests hypotheses) | Psychology Dissertation: Testing whether different study environments (quiet vs. noisy library) affect exam scores by randomly assigning students to each condition and measuring performance. |

Survey | Standardize & Generalize: Collect standardized data (often quantitative) from a representative sample of a larger population using questionnaires. | Describing characteristics, attitudes, or behaviours of a population; identifying patterns/trends. | Deductive (Tests relationships/theories) | Marketing Dissertation: Distributing online questionnaires to 500 consumers to measure brand loyalty and purchasing habits across different age groups. |

Case Study | Depth & Context: In-depth investigation of a single instance (person, group, org, event) using multiple evidence sources (interviews, docs, obs). | Gaining holistic, deep understanding of a complex phenomenon in its real-world context. | Inductive/Abductive (Explore/Explain) | Business Dissertation: Studying one startup company's failure through interviews with founders, analysis of financial records, and observation of workplace culture. |

Action Research | Solve & Improve: Iterative cycles (Plan → Act → Observe → Reflect) focused on solving a specific practical problem within an organization/community. Involves collaboration with practitioners. | Improving practice, solving immediate problems, generating actionable knowledge in situ. | Abductive (Solve puzzles) | Education Dissertation: Working with teachers to implement new teaching methods (Plan), applying them in classrooms (Act), observing student engagement (Observe), and refining techniques (Reflect). |

Grounded Theory | Build Theory Inductively: Systematically develops theory "from the ground up" through rigorous coding and analysis of qualitative data (usually interviews/obs). | Generating new theory about a social process where little existing theory exists. | Inductive (Builds theory from data) | Sociology Dissertation: Conducting interviews with remote workers to develop a new theory about how work-life boundaries are negotiated in digital workplaces. |

Ethnography | Immerse & Understand: Long-term, immersive engagement within a specific social group/setting to understand its culture, meanings, and practices from an insider perspective. | Deeply understanding culture, social processes, and shared meanings in natural settings. | Inductive (Explores meanings) | Anthropology Dissertation: Living with a rural farming community for 6 months to document traditional agricultural practices and their cultural significance. |

Archival Research | Analyse Existing Data: Systematically examines existing documents, records, or datasets (historical, gov't, organizational, digital). | Understanding past events, trends, contexts, or analysing patterns without direct interaction. | Deductive/Inductive (Test/Explore) | History Dissertation: Analyzing 19th-century prison records and government reports to study the evolution of criminal rehabilitation policies. |

How to Choose: Selecting Your Blueprint

Choosing the right Strategy is about finding the best fit between your Approach, your Research Question, and practical realities. Ask yourself these critical questions:

"What strategy BEST implements my chosen Research Approach?"

Need high control & cause-effect? → Experiment.

Need to describe/measure relationships in a population? → Survey.

Need to test a theory in a real-world context? → Case Study (less common for pure deduction, but possible).

Need deep understanding of culture/group? → Ethnography.

Need to generate new theory about a process? → Grounded Theory.

Need holistic understanding of a complex phenomenon in context? → Case Study.

Need to solve a practical problem collaboratively? → Action Research.

Need the best explanation for a complex real-world puzzle? → Case Study.

Deductive (Testing Theory/Hypotheses):

Inductive (Building Theory/Exploring Meanings):

Abductive (Solving Problems/Explaining Puzzles):

"What strategy is MOST appropriate for my specific Research Question?"

Question asks "What is the effect of X on Y?" → Experiment (ideal) or Survey (correlation).

Question asks "What are the experiences/perceptions of X?" or "How is Y culture constructed?" → Ethnography, Case Study, or Grounded Theory.

Question asks "How can we improve X process/solve Y problem?" → Action Research or Case Study.

Question asks "What happened in the past?" or "What trends exist in existing data?" → Archival Research.

Question asks "How does this complex system/phenomenon work in context?" → Case Study.

"What strategy is MOST FEASIBLE given my context?"

Access: Can you get permission to manipulate variables (Experiment)? Immmerse in a group (Ethnography)? Access sensitive documents (Archival)? Collaborate with an organization (Action Research)?

Time: Do you have months/years for immersion (Ethnography, Longitudinal)? Or weeks/months (Survey, Case Study, Experiment)?

Resources: Do you need expensive equipment (Experiment)? Software for analysis (Survey, Grounded Theory)? Travel funds (Ethnography, Case Study)?

Skills: Are you trained in experimental design? Statistical analysis? Qualitative interviewing/coding? Historical analysis?

Ethics: Can your strategy be conducted ethically? (e.g., Experiments manipulating human behavior require strict ethical scrutiny).

Critical Reminder

No "Best" Strategy: Only the most appropriate for your specific question, approach, and constraints.

Justify Rigorously: In your methodology chapter, you must explicitly state why your chosen strategy is the optimal fit, linking it back to your Approach, Philosophy, and Research Question.

Consider Hybrid Cautiously: While pure strategies are common, sometimes elements blend (e.g., a Case Study using surveys within it). If you do this, justify why the hybrid is necessary and how the elements fit together coherently.

Your Research Strategy is the concrete plan that transforms your philosophical and approach decisions into actionable research. Choosing wisely ensures your dissertation is not only theoretically sound but also practically achievable and capable of answering your research question effectively. It’s the third essential "peel" of the Research Onion.

Layer 4: Methodological Choices (The "Scope" - "How Many Methods Will I Use?")

What It Is: Deciding Your Methodological Scope

Methodological Choice is the strategic decision about the number and type of research methods you will employ in your study. It answers: "Will I use one method only, multiple methods of the same type, or a blend of different types (qualitative and quantitative)?" This layer defines the breadth and diversity of your data collection toolkit. While your Strategy (Layer 3) sets the overall plan, Methodological Choice determines how many tools you’ll use from that plan’s toolbox.

Why It Matters: Balancing Depth, Breadth, and Rigor

Your Methodological Choice profoundly shapes your research’s credibility, depth, and feasibility. It matters because:

It Determines Data Richness:

Mono Method: Offers depth in one area but limited perspective.

Multi-method/Mixed Methods: Provides richer, more nuanced insights by capturing different facets of the phenomenon.

It Impacts Analytical Complexity:

Mono Method: Simpler analysis (e.g., only thematic analysis or only statistical tests).

Multi-method/Mixed Methods: Requires integrating findings from different methods, adding complexity but potentially strengthening conclusions.

It Affects Triangulation & Validity:

Using multiple methods (especially Mixed Methods) allows triangulation – cross-verifying findings from different sources or perspectives. This enhances the validity (trustworthiness) of your conclusions.

It Influences Feasibility:

More methods = More time, resources, skills, and ethical considerations. Mono Method is often more manageable for novice researchers within tight deadlines.

It Must Align with Philosophy & Strategy:

A mismatch here creates incoherence. For example, a strict Positivist philosophy might struggle to justify integrating subjective qualitative data (Mixed Methods).

Key Choices Explained: Defining Your Methodological Toolkit

Here are the three core methodological choices, detailing their scope, purpose, and implications:

Choice | Definition & Scope | Primary Goal | Key Characteristics | Example Combinations |

Mono Method | Using only ONE research method throughout the entire study. | Focused Depth or Broad Simplicity |

| Only Interviews Only Surveys Only Document Analysis |

Mixed Methods | Systematically combining BOTH qualitative AND quantitative methods within a single study. Methods are integrated during collection, analysis, and/or interpretation. | Complementary Strengths (Breadth + Depth) |

| Survey (Quant) + Interviews (Qual) Experiments (Quant) + Focus Groups (Qual) Stats (Quant) + Case Study (Qual) |

Multi-method | Using MULTIPLE methods, but ALL are either qualitative OR quantitative (not a mix). Methods may be sequential/concurrent but not necessarily deeply integrated. | Triangulation within one paradigm |

| Interviews + Focus Groups (both Qual) Survey + Archival Data (both Quant) Observations + Diaries (both Qual) |

How to Choose: Selecting Your Methodological Scope

Choosing the right scope requires balancing your research needs with practical constraints while ensuring alignment with your Philosophy and Strategy. Ask yourself:

"Will ONE method give me a COMPLETE enough answer?"

When to Choose:

Your research question is highly focused (e.g., "What are employees' perceptions of the new policy?" → Interviews alone may suffice).

Your Strategy inherently relies on one method (e.g., a pure Ethnography relies on immersion/observation; a standardized Survey relies on questionnaires).

You have significant time/resource constraints.

Your Philosophy strongly aligns with one method type (e.g., Positivism often aligns well with quantitative Mono Method surveys/experiments).

If YES: Consider Mono Method.

"Do I need BOTH NUMBERS (breadth/generalizability) AND WORDS (depth/understanding) to fully answer my question?"

When to Choose:

Your research question has distinct sub-questions requiring different data types (e.g., "What is the usage rate of our app? (Quant) AND Why do users engage/disengage? (Qual)").

You need to contextualize or explain quantitative findings with qualitative insights (or vice-versa).

You aim to overcome the limitations of one method with the strengths of another (e.g., Surveys show what people think; Interviews explain why).

Crucially: Your Philosophy supports integration (e.g., Pragmatism explicitly prioritizes "what works" and readily embraces Mixed Methods). Some forms of Realism can also justify it.

If YES: Consider Mixed Methods.

"Do I need MULTIPLE PERSPECTIVES/SOURCES within the SAME TYPE of data (e.g., multiple qualitative methods) to strengthen my findings?"

When to Choose:

You want triangulation within one paradigm (e.g., using Interviews and Focus Groups (both Qual) to see if themes hold across different group dynamics; using Surveys and Archival Stats (both Quant) to cross-check trends).

Your Strategy benefits from multiple data sources of the same type (e.g., a Case Study often uses Interviews + Docs + Obs – all Qual).

Your Philosophy values depth but within one worldview (e.g., Interpretivism using multiple qualitative methods to build a rich picture; Positivism using multiple quantitative measures to ensure reliability).

Mixed Methods feels too complex or philosophically misaligned, but one method feels insufficient.

If YES: Consider Multi-method.

"CRUCIALLY: Does this choice align with my Philosophy and Strategy?"

Philosophy Alignment:

Positivism: Often favours Mono Method (Quant) or Multi-method (Quant). Mixed Methods (Qual+Quant) can be challenging to justify philosophically unless framed carefully (e.g., using qual only to explain quant findings).

Interpretivism: Often favours Mono Method (Qual) or Multi-method (Qual). Mixed Methods is possible but requires strong justification for integrating quant data meaningfully.

Pragmatism: Strongly supports Mixed Methods ("Use what works!"). Also supports Mono/Multi-method if appropriate.

Realism: Can support Mixed Methods (acknowledging different layers of reality) or Multi-method.

Postmodernism: Often leans towards Multi-method (Qual) to explore diverse discourses/narratives.

Strategy Alignment:

Experiment/Survey: Often naturally Mono Method or Multi-method (Quant).

Case Study: Frequently Multi-method (Qual) or Mixed Methods (e.g., Qual interviews + Quant context data).

Ethnography/Grounded Theory: Typically Mono Method (Qual) or Multi-method (Qual).

Action Research: Often Mixed Methods (Quant measures of outcomes + Qual insights into process) or Multi-method (Qual).

Archival Research: Often Mono Method or Multi-method (using different doc types).

Critical Considerations for Feasibility

Time & Resources: Mixed Methods is the most demanding. Be realistic about your dissertation timeline and access to participants/data.

Skills: Do you have (or can you quickly learn) the skills needed for all chosen methods (e.g., statistical analysis and qualitative coding)?

Integration (Mixed Methods): How exactly will you connect the qualitative and quantitative findings? (e.g., Qual explains Quant? Quant validates Qual? They converge/diverge?). This needs explicit planning.

Sampling: How will sampling work across methods? (e.g., Same participants? Different? Purposive vs. Random?).

Remember: Your Methodological Choice isn’t about using as many methods as possible. It’s about using the right number and type of methods to most effectively, coherently, and feasibly answer your research question, while staying true to your foundational Philosophy and Strategy. It’s the fourth essential "peel" of the Research Onion.

Layer 5: Time Horizon (The "Duration" - "When Will the Data Be Collected?")

What It Is: The Temporal Dimension of Your Study

Time Horizon refers to when and for how long you collect data in your research. It answers a fundamental question: "Will my research capture a single moment in time or track developments over an extended period?" This layer defines the temporal scope of your investigation, determining whether you're taking a "snapshot" or creating a "movie" of your subject.

Why It Matters: Capturing Moments vs. Tracking Change

Your Time Horizon choice is critical because it fundamentally shapes what you can learn and how feasible your study is:

It Defines What You Can Discover:

Cross-Sectional: Reveals the state of affairs at one specific point (e.g., current opinions, present conditions, existing relationships). It answers "What is happening now?"

Longitudinal: Reveals patterns of change, development, stability, or causality over time. It answers "How did this come to be?", "Is this changing?", "What are the long-term effects?"

It Impacts Feasibility Dramatically:

Cross-Sectional: Generally faster, cheaper, and simpler to conduct. Data collection happens within a defined, relatively short window.

Longitudinal: Often slow, expensive, complex, and logistically challenging. It requires sustained access to participants/settings, consistent methods over time, and significant resources. Attrition (participants dropping out) is a major risk.

It Influences Validity & Generalizability:

Cross-Sectional: Can be highly valid for describing the present moment but cannot establish causality or change over time. Findings might be time-bound.

Longitudinal: Stronger for establishing temporal precedence (A happened before B, suggesting possible causality) and observing developmental processes. However, findings can be influenced by historical events or participant maturation.

It Must Align with Your Research Question and Strategy:

Asking about "current perceptions" but choosing Longitudinal is inefficient. Asking about "development over time" but choosing Cross-Sectional is impossible. Your Strategy (e.g., Experiment, Case Study, Ethnography) also has inherent time implications.

Key Horizons Explained: Your Temporal Options

Here are the two core time horizons, detailing their scope, purpose, and implications:

Time Horizon | Definition & Data Collection Window | Primary Purpose | Key Characteristics | Examples |

Cross-Sectional | Data collected at ONE specific point in time (or a very short, defined period). | Describe the "here and now" |

|

|

Longitudinal | Data collected repeatedly over an extended period (months, years, decades). | Study change, development, trends, or causality over time |

|

|

How to Choose: Selecting Your Temporal Scope

Choosing the right Time Horizon requires aligning your research question's needs with practical realities. Ask yourself:

"What does my RESEARCH QUESTION fundamentally ask about TIME?"

Examples: "What are current employee attitudes towards remote work?" "What is the market share of Brand X today?" "How do customers perceive our new service right now?"

Likely Fit: Cross-Sectional. You need a snapshot of the current situation.

Examples: "How has employee morale evolved over the past year since the merger?" "What factors influence career progression in this industry over a 5-year period?" "What are the long-term impacts of this educational intervention?"

Likely Fit: Longitudinal. You need to track developments over time to answer this.

Does it focus on the PRESENT STATE?

Does it focus on CHANGE, DEVELOPMENT, or LONG-TERM EFFECTS?

"What does my chosen RESEARCH STRATEGY imply about TIME?"

Experiment: Often Cross-Sectional (measuring effects immediately after manipulation), but can be Longitudinal if tracking effects over time.

Survey: Can be either. Cross-Sectional is most common (e.g., opinion polls). Longitudinal surveys track changes in attitudes/behaviors (e.g., panel studies).

Case Study: Can be either. A Cross-Sectional case study examines a case at one point. A Longitudinal case study tracks the case over time (e.g., studying a company through a crisis year).

Action Research: Often inherently Longitudinal due to its iterative cycles (Plan-Act-Observe-Reflect repeated over time).

Grounded Theory: Typically involves Longitudinal data collection (e.g., repeated interviews/observations) to capture evolving processes.

Ethnography: Usually Longitudinal, requiring long-term immersion to understand culture and social processes.

Archival Research: Can be either. Analyzing documents from a single year = Cross-Sectional. Analyzing documents spanning decades = Longitudinal.

"PRACTICAL REALITY: Do I have the necessary TIME, RESOURCES, and ACCESS?"

Time: How long is your dissertation timeline? A Longitudinal study often takes years – likely impossible for a typical 6-12 month Master's dissertation. Cross-Sectional is far more feasible within tight deadlines.

Resources: Can you afford sustained data collection (travel, participant incentives, researcher time) over months/years? Longitudinal studies are significantly more expensive.

Access: Can you guarantee access to the same participants, organization, or data source repeatedly over time? Longitudinal studies rely heavily on continued cooperation and low attrition.

Skills: Do you have the skills to manage complex longitudinal data (tracking, analysis of change over time)?

Critical Decision-Making Tip

Be Brutally Honest About Feasibility: Many brilliant research questions require a longitudinal approach. If your dissertation timeframe and resources make this impossible, you must refine your question to fit a Cross-Sectional design. For example:

Original (Longitudinal): "How has social media usage impacted adolescent mental health over the last 5 years?"

Revised (Cross-Sectional): "What is the current relationship between social media usage patterns and self-reported mental health among adolescents?"

Justify Rigorously: In your methodology, explicitly state your chosen Time Horizon and justify it based on:

The precise requirements of your research question.

The inherent demands of your chosen Research Strategy.

The practical constraints and feasibility within your dissertation context.

Your Time Horizon is the temporal framework that dictates whether you capture a static image or a dynamic process. Choosing wisely ensures your research design is not only aligned with your goals but also realistically achievable within your means. It’s the fifth essential "peel" of the Research Onion.

Layer 6: Techniques and Procedures (The Innermost Core - "Exactly How Will I Collect & Analyse the Data?")

What It Is: Your Hands-On Toolkit

Techniques and Procedures represent the innermost core of the Research Onion, where your abstract plans transform into concrete action. This layer specifies exactly how you will:

Collect Data: The specific methods you use to gather raw information from your chosen sources (participants, documents, observations, etc.).

Analyse Data: The step-by-step procedures you use to process, interpret, and make sense of that collected data to answer your research questions.

This is the most practical, detailed, and operational layer of your research design. While outer layers set the "why" and "what," this layer defines the "how" in precise terms.

Why It Matters: Where Validity Takes Shape

This layer is absolutely critical because it's where the validity (trustworthiness) and reliability (consistency) of your findings are directly established or undermined. It matters because:

It Implements Your Entire Design: No matter how coherent your Philosophy, Approach, Strategy, etc., are, poor technique choices or sloppy execution will invalidate your results. This layer is where your design meets reality.

It Determines Data Quality: The appropriateness and rigor of your data collection techniques directly impact the richness, accuracy, and relevance of your data. Garbage in = garbage out.

It Shapes Meaningful Insights: Your analysis procedures determine whether you can legitimately extract meaningful patterns, relationships, or themes from your data to answer your research questions. Inappropriate analysis leads to flawed conclusions.

It Requires Specificity & Transparency: You must describe your techniques and procedures in detail in your methodology chapter so others can evaluate your rigor and potentially replicate your study. Vague descriptions here are a major red flag for examiners.

It Must Align Perfectly with Outer Layers: Your choices here are not independent. They are the logical endpoint of every decision made in Layers 1-5. A mismatch here creates incoherence and weakens your entire argument.

Key Components Explained: Your Data Toolkit

This layer has two essential components: Data Collection Techniques (gathering) and Data Analysis Procedures (interpreting).

A. Data Collection Techniques: Gathering Your Raw Information

These are the specific methods you use to obtain your primary data. Your choice depends entirely on your Strategy, Methodological Choice, and Research Question.

Technique Category | Specific Examples | Best Suited For |

Interaction-Based |

| Exploring perspectives, experiences, opinions (Qual). Common in Case Studies, Ethnography, Grounded Theory. |

Observation-Based |

| Understanding behaviors, interactions, processes in natural settings (Qual). Core to Ethnography, Action Research. |

Questionnaire-Based |

| Gathering standardized data from many people efficiently (Primarily Quant). Core to Survey Strategy. |

Document/Artifact-Based |

| Analyzing existing records, historical trends, or visual representations (Qual/Quant). Used in Archival Research, Case Studies, Historical Research. |

Experimental |

| Testing cause-effect relationships under controlled conditions (Primarily Quant). Core to Experiment Strategy. |

B. Data Analysis Procedures: Making Sense of Your Data

These are the systematic processes you apply to your collected data to identify patterns, answer questions, and develop conclusions. Your choice depends on your data type (Quant/Qual/Mixed), Philosophy, Approach, and Research Questions.

Analysis Type | Specific Procedures | Purpose & Philosophy Link |

Quantitative Analysis |

| Describe patterns, test relationships/hypotheses, generalize findings. Strong link to Positivism/Deductive (testing theories). |

Qualitative Analysis |

| Explore meanings, experiences, perspectives, social processes, develop theory. Strong link to Interpretivism/Inductive (building understanding from data). |

How to Choose: Selecting Your Specific Tools

Choosing techniques and procedures requires rigorous alignment with your outer layers and practical considerations. Do NOT pick methods you "like" or find easy! They must be the most appropriate for your design.

For Data Collection Techniques: Ask Yourself:

"What techniques are BEST SUITED to my chosen Research Strategy and Methodological Choice?"

Strategy: Case Study? → Often Interviews + Document Analysis + (maybe) Observation (Multi-method Qual or Mixed).

Strategy: Survey? → Questionnaires (Quant Mono Method).

Strategy: Experiment? → Controlled Observation + Measurement (Quant Mono Method).

Strategy: Ethnography? → Participant Observation + Informal Interviews (Qual Multi-method).

Methodological Choice: Mixed Methods? → Requires at least one Qual technique AND one Quant technique (e.g., Surveys + Interviews).

Methodological Choice: Multi-method (Qual)? → Multiple Qual techniques (e.g., Interviews + Focus Groups).

"What techniques will give me ACCESS to the SPECIFIC DATA I need to answer my research questions?"

Need deep personal experiences? → In-depth Interviews, Diaries.

Need group dynamics? → Focus Groups.

Need observable behaviors? → Observation.

Need broad attitudes from many? → Surveys.

Need historical context? → Archival Research, Document Analysis.

Need to test cause-effect? → Experiments.

"What am I SKILLED AT (or can realistically learn)? What are the ETHICAL considerations?"

Skills: Do you know how to design reliable surveys? Conduct unbiased interviews? Run statistical software? Perform thematic coding? Be honest about your capabilities and training needs.

Ethics: Consider sensitivity (e.g., trauma interviews require special skills), confidentiality (e.g., focus groups risk breaches), informed consent, anonymity, and potential harm. Some techniques carry higher ethical burdens.

For Data Analysis Procedures: Ask Yourself:

"What analysis procedures are APPROPRIATE for the TYPE of data I'm collecting?"

Quantitative Data (Numbers, Stats): Requires Quantitative Analysis (Descriptive/Inferential Stats, Quant Content Analysis). You cannot meaningfully analyze numerical survey data with Thematic Analysis.

Qualitative Data (Words, Text, Observations): Requires Qualitative Analysis (Thematic Analysis, Discourse Analysis, IPA, etc.). You cannot statistically test interview transcripts without quantifying them first (which changes their nature).

Mixed Methods Data: Requires BOTH Quant AND Qual analysis procedures, plus a plan for integrating the findings (e.g., Qual explains Quant; Quant validates Qual; they converge/diverge).

"What procedures will help me answer my SPECIFIC RESEARCH QUESTIONS?"

Question asks "What is the relationship between X and Y?" → Likely needs Inferential Statistics (e.g., correlation, regression).

Question asks "What are the experiences of X?" → Likely needs Thematic Analysis or IPA.

Question asks "How is power constructed in Y discourse?" → Likely needs Discourse Analysis.

Question asks "How does the Z process develop?" → Likely needs Grounded Theory Coding or Narrative Analysis.

"What procedures ALIGN with my Philosophy and Approach?"

Philosophy: Positivism / Approach: Deductive? → Quantitative Analysis (Stats) is the natural fit – testing hypotheses with measurable data.

Philosophy: Interpretivism / Approach: Inductive? → Qualitative Analysis (Thematic, IPA, etc.) is the natural fit – exploring meanings and building understanding from rich data.

Philosophy: Pragmatism? → Can justify Quant, Qual, or Mixed analysis – focus is on what works to answer the question.

The Golden Rule: No Isolation!

CRUCIALLY: Your techniques and procedures MUST logically follow from ALL the outer layers.

You cannot choose Interviews (Collection) and Thematic Analysis (Analysis) if your Philosophy is Positivism and Approach is Deductive. This is a fundamental mismatch.

You cannot choose Experiments (Collection) and Inferential Statistics (Analysis) if your Strategy is Ethnography.

You cannot choose Surveys (Collection) and Thematic Analysis (Analysis) unless you have a very strong justification for treating open-ended survey responses qualitatively and this aligns with your overall design (e.g., a Mixed Methods study).

Every choice at this core layer must be justifiable as the logical endpoint of the journey you started at Layer 1 (Philosophy). In your methodology chapter, explicitly state your chosen techniques and procedures and justify each one by linking it back to your Strategy, Methodological Choice, data type needs, research questions, Philosophy, and Approach. This demonstrates rigorous, coherent thinking and builds confidence in your findings.

Part C: Research Onion Compatibility Guide for Novice Researchers

Important Note: This guide shows the safest combinations for beginners. Advanced studies may justify exceptions, but novices should follow these rules to ensure methodological coherence.

Layer 1: Philosophy (Foundation)

Philosophy | Compatible Approaches | Incompatible Approaches | Why? |

Positivism | Deductive | Inductive, Abductive | Concise Rationale: Focuses on testing objective truths, not building theory from scratch or solving puzzles pragmatically. Detailed Incompatibility: Positivism demands testing objective, measurable theories (deductive). Induction builds theory subjectively from scratch; abduction solves puzzles pragmatically. Both reject positivism’s core goal of verifying universal laws. |

Interpretivism | Inductive | Deductive | Concise Rationale: Focuses on exploring subjective meanings, not testing pre-defined theories. Detailed Incompatibility: Interpretivism explores subjective meanings (inductive). Deduction tests pre-defined theories objectively, ignoring the lived experiences interpretivism prioritizes. |

Pragmatism | Abductive, Mixed Methods | Strict Deductive/Inductive | Concise Rationale: Prioritizes practical solutions over philosophical purity. Detailed Incompatibility: Pragmatism prioritizes practical solutions over philosophical purity. Strict deduction/induction adhere rigidly to one path, while pragmatism blends approaches to solve problems. |

Realism | Deductive, Abductive | Pure Inductive | Concise Rationale: Believes in objective reality but imperfect access; needs structured testing or explanation. Detailed Incompatibility: Realism acknowledges an objective reality but imperfect human access. Induction builds theory without testing/explaining underlying structures, contradicting realism’s focus. |

Postmodernism | Inductive (Critical) | Deductive | Concise Rationale: Rejects grand theories; deconstructs truths rather than testing them. Detailed Incompatibility: Postmodernism deconstructs "truths" (inductive). Deduction tests grand theories as objective, which postmodernism rejects as power-laden narratives. |

Layer 2: Approach (Reasoning Path)

Approach | Compatible Strategies | Incompatible Strategies | Why? |

Deductive | Experiment, Survey, Archival Research | Ethnography, Grounded Theory | Concise Rationale: Requires testing hypotheses with measurable data, not exploring cultures or building theory inductively. Detailed Incompatibility: Deduction requires measurable data to test hypotheses. Ethnography/grounded theory prioritize exploration and theory-building from subjective data, not hypothesis-testing. |

Inductive | Ethnography, Grounded Theory, Case Study | Experiment, Survey | Concise Rationale: Needs rich, exploratory data to build theory, not controlled testing or broad quantification. Detailed Incompatibility: Induction builds theory from rich, exploratory data. Experiments/surveys impose pre-defined structures (e.g., controlled variables, fixed questions), stifling open-ended discovery. |

Abductive | Action Research, Case Study | Experiment, Survey | Concise Rationale: Focuses on solving puzzles in real-world contexts, not controlled hypothesis testing. Detailed Incompatibility: Abduction solves real-world puzzles iteratively. Experiments/surveys use controlled, one-off designs that can’t adapt to unexpected findings or context. |

Layer 3: Strategy (Blueprint)

Strategy | Compatible Techniques | Incompatible Techniques | Why? |

Experiment | Controlled observation, measurement, surveys | Unstructured interviews, ethnography | Concise Rationale: Requires manipulation of variables in controlled settings; not open-ended exploration. Detailed Incompatibility: Experiments require manipulating variables in controlled settings. Unstructured interviews/ethnography rely on open-ended exploration in natural environments, destroying control. |

Survey | Questionnaires, structured interviews | Participant observation, diaries | Concise Rationale: Needs standardized data from large samples; not immersive or personal narratives. Detailed Incompatibility: Surveys need standardized data from large samples. Participant observation/diaries generate idiosyncratic, personal data that can’t be standardized or generalized. |

Case Study | Interviews, docs, observation, surveys (mixed) | Strict lab experiments | Concise Rationale: Requires holistic, contextual data; not artificial isolation of variables Detailed Incompatibility: Case studies require holistic, real-world context. Lab experiments artificially isolate variables, stripping away the context case studies need. |

Ethnography | Participant observation, unstructured interviews | Surveys, experiments | Concise Rationale: Demands long-term immersion; not detached measurement or testing. Detailed Incompatibility: Ethnography demands long-term immersion in natural settings. Surveys/experiments are detached, one-time tools that disrupt immersion. |

Grounded Theory | Interviews, observation (iterative) | Pre-defined surveys | Concise Rationale: Needs open-ended data to build theory; not fixed-response instruments. Detailed Incompatibility: Grounded theory builds theory iteratively from open data. Pre-defined surveys impose fixed questions, preventing emergent themes. |

Action Research | Interviews, observations, meetings | Archival research alone | Concise Rationale: Requires iterative collaboration; not solely historical analysis. Detailed Incompatibility: Action research needs iterative collaboration to solve problems. Archival research is static and historical, lacking real-time engagement. |

Archival Research | Document analysis, datasets | Interviews, experiments | Concise Rationale: Focuses on existing records; not new data generation or manipulation. Detailed Incompatibility: Archival research analyses existing records. Interviews/experiments generate new data, conflicting with its focus on historical/secondary sources. |

Layer 4: Methodological Choice (Scope)

Choice | Compatible Philosophies | Incompatible Philosophies | Why? |

Mono Method | Positivism, Interpretivism | Pragmatism (usually) | Concise Rationale: Pragmatism favours mixing methods; mono-method may limit problem-solving. Detailed Incompatibility: Pragmatism mixes methods to solve problems. Mono-method uses one approach, limiting the flexibility pragmatism requires. |

Mixed Methods | Pragmatism, Realism | Strict Positivism/Interpretivism | Concise Rationale: Combines quant/qual; conflicts with purist philosophies. Detailed Incompatibility: Mixed methods blend quant/qual data. Strict positivism/interpretivism prioritize one paradigm (objective measurement OR subjective meaning), rejecting integration. |

Multi-method | Interpretivism, Positivism | Postmodernism (often) | Concise Rationale: Uses multiple methods of same type; Postmodernism may reject methodological consistency. Detailed Incompatibility: Multi-method uses multiple methods of the same type (e.g., 2+ qualitative). Postmodernism rejects methodological consistency, viewing it as artificially imposing order. |

Layer 5: Time Horizon (Duration)

Horizon | Compatible Strategies | Incompatible Strategies | Why? |

Cross-Sectional | Survey, Experiment, Archival Research | Ethnography, Grounded Theory | Concise Rationale: Captures a snapshot; not long-term cultural/processual study. Detailed Incompatibility: Cross-sectional designs capture a snapshot in time. Ethnography/grounded theory require longitudinal engagement to study processes/cultural evolution. |

Longitudinal | Ethnography, Grounded Theory, Action Research | Simple surveys/experiments | Concise Rationale: Tracks change over time; not one-off measurement. Detailed Incompatibility: Longitudinal designs track change over time. Simple surveys/experiments are one-off tools that can’t capture development or evolution. |

Layer 6: Techniques & Procedures (Tools)

Technique/Procedure | Compatible With | Incompatible With | Why? |

Interviews + Thematic Analysis | Interpretivism, Inductive, Case Study | Positivism, Deductive | Concise Rationale: Explores subjective meanings; not for testing objective hypotheses. Detailed Incompatibility: Interviews/thematic analysis explore subjective meanings. Positivism/deduction require objective, measurable data to test hypotheses – qualitative analysis is too interpretive. |

Experiments + Inferential Stats | Positivism, Deductive, Experiment | Ethnography, Interpretivism | Concise Rationale: Tests cause-effect; not for cultural immersion or meaning-making. Detailed Incompatibility: Experiments/stats test cause-effect objectively. Ethnography/interpretivism study subjective cultural meanings – experiments destroy natural context. |

Surveys + Statistical Tests | Positivism, Deductive, Survey | Interpretivism, Grounded Theory | Concise Rationale: Quantifies patterns; not for exploring lived experiences. Detailed Incompatibility: Surveys/stats quantify patterns objectively. Interpretivism/grounded theory prioritize exploring lived experiences – statistics reduce narratives to numbers. |

Open-Ended Surveys + Thematic Analysis | Mixed Methods, Pragmatism | Mono-Method Positivism | Concise Rationale: Qual analysis of quant data requires mixed-methods justification. Detailed Incompatibility: Open-ended surveys generate qualitative data. Mono-method positivism requires purely quantitative analysis – thematic analysis violates this. |

Participant Observation + Narrative Analysis | Ethnography, Interpretivism, Inductive | Experiment, Deductive | Concise Rationale: Studies culture/stories; not controlled variable testing. Detailed Incompatibility: Observation/narrative analysis study culture/stories in context. Experiments/deduction control variables artificially, destroying natural settings. |

Document Analysis + Content Analysis (Qual) | Archival Research, Case Study, Inductive | Experiment, Deductive | Concise Rationale: Interprets texts; not for measuring causal relationships. Detailed Incompatibility: Document/content analysis interpret texts. Experiments/deduction measure causal relationships – documents can’t establish cause-effect. |

Golden Rules for Novice Researchers

Follow the Flow: Start with Philosophy (Layer 1) → move inward. Each layer must logically connect to the next.

Avoid "Frankenstein" Combos: Don’t mix incompatible elements (e.g., Positivism + Thematic Analysis) unless you’re an expert.

Feasibility First: Choose methods you can realistically complete (e.g., avoid longitudinal ethnography in a 3-month project).

Write It Down: In your methodology chapter, explain each layer’s choice and link it to the next:

"Given my Interpretivism (Layer 1), I used Induction (Layer 2), leading to a Case Study (Layer 3)... with Interviews analyzed thematically (Layer 6)."

Final Tip: Sketch your Research Onion choices. If arrows don’t flow logically from Philosophy → Techniques, revise!

Disclaimer

While this guide covers 95% of novice projects, advanced researchers may justify exceptions (e.g., using qualitative data to explain quantitative results in a positivist study). Nevertheless, these require deep philosophical justification and are not recommended for beginners. Stick to these rules for a safe, coherent methodology.