Introduction

One of the biggest struggles students face in dissertations is not the writing, but the very first step, framing a solid research question. This challenge is particularly evident across UK universities, where supervisors often highlight recurring issues such as:

- The question is too broad to answer within the word count and timeframe of a UK dissertation.

- Poor alignment with the chosen domain or methodology which is a common reason for feedback in proposal reviews.

- Vague wording that reads more like a topic than a researchable question.

- Attempting to cover too many areas at once, which UK examiners may criticise as “lacking criticality” or “focus.”

In the UK universities, a well-defined research question is essential not only for guiding your study but also for meeting the QAA (Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education) standards of clarity, originality, and feasibility. Universities such as the University of Manchester, King’s College London, or the University of Sheffield consistently emphasize that one strong central research question, supported by two or three sub-questions, is the best way to score a higher grade in a dissertation. Whether you are pursuing your degree in the UK, the US, or at any international university, this guide is designed to help you turn uncertainty into clarity by creating a research question that is precise, well-structured, and research-ready.

What Is a Research Question?

Definition of Research Question: A good research question is a short, narrow statement defining the exact subject or problem that a study aims to examine or address. It specifies the area of investigation by explicitly stating what the researcher wishes to learn or know, and it is usually stated in the format of a direct question or testable hypothesis.

Most dissertations in the UK are guided by one central research question, the “big guiding question”, supported by two or three sub-questions if necessary. The central question provides direction for the entire project, while the sub-questions allow you to break it into manageable parts, such as exploring a particular factor, comparing approaches, or examining context.

One central research question – the big guiding question.

Two or three sub-questions(Optional) – smaller, specific questions that break the main one into manageable parts.

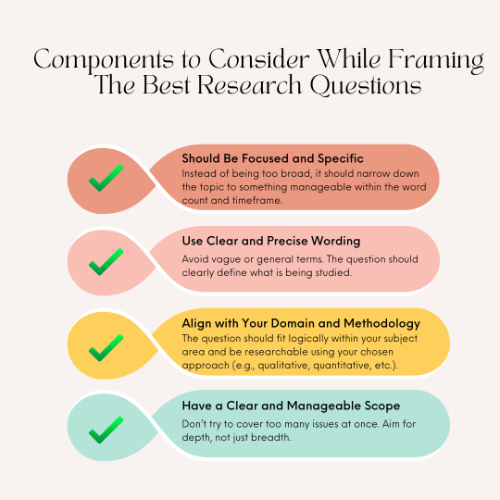

What makes a good research question?

A good research question has the following characteristics:

- Specific and direct: It is too specific to be misunderstood and too specific to be answered without including too much or too little information.

- Researchable: The question is researchable; it can be studied using available data or sources with available time, resources, and practical limitations.

- Complex and Controversial: It cannot be answered by a simple yes/no or a fact available on the internet or in books, but rather needs to be analyzed, synthesized or interpreted.

- Relevant and significant: It deals with a significant issue or gap of knowledge of interest to the field or the society and contributes original thoughts or perceptions. In UK universities, this idea is often described as making a “contribution to knowledge”, which simply means your dissertation should offer something new: a fresh perspective, new data, or applying an idea to a different context.

- Practical: It can be ethically and methodologically possible to study with reasonable expertise, budget, and time.

- Well-grounded: It draws upon available theoretical and empirical knowledge in the literature to provide context and justification.

- Specific concepts and variables: It clearly outlines the main terms and variables that are involved and often contains a target population or situation.

- Feasible and Ethical: The question should be realistically researchable, given your resources, and also meet your university’s ethical standards. For UK dissertations, this often means considering whether your project could gain Research Ethics Committee approval.

How to Write Research Questions

Learning how to write a good research question is one of the most important skills in academic writing. A well-framed question gives direction to your dissertation, defines the scope of your study, and ensures that your research is both focused and meaningful. In the next steps, we’ll show you how to write a research question step by step, starting from a broad idea and narrowing it down into a clear, testable question.

Step 1 — Begin with a Topic That Matters to You

The first step in writing a research question is choosing your topic. This can come from two places:

1. Your own interest within your academic domain — If you have the freedom to choose, start with a domain that genuinely excites you. You’ll be working on this project for weeks (sometimes months), so it’s much easier to stay motivated if the topic sparks curiosity.

At UK universities, most dissertations are written within the main subject areas of study. These often include:

Business and Management

Nursing and Health Sciences

Education

Engineering

Computer Science and more

Your dissertation topic will usually fall into one of these broad domains, depending on your degree programme. Within each area, you still have the freedom to choose a focus that matches your personal interests and career goals.

For example:

In the nursing domain, it might be improving patient care or preventing hospital infections.

In the business domain, it could be leadership styles or employee motivation in startups.

In the computer science domain, maybe testing a new AI algorithm or working on a cloud environment

In the education domain, it could be flipped classrooms or online learning engagement.

In the engineering domain, perhaps renewable energy solutions or smart city infrastructure.

2. The assignment brief from your university — If the topic is given, don’t treat it like a limitation. Instead, read the brief carefully to see exactly what’s being asked.

Are you expected to analyze a problem?

Compare two approaches?

Or evaluate the effectiveness of a method or policy?

Action step: Write down your broad topic idea, either from your interest/domain or straight from your brief. Don’t worry if it feels vague right now. In the next steps, you’ll sharpen it into something specific and researchable.

Example Table: Writing Down a Broad Topic

Source of Topic | Broad Topic Idea (as written by student) | Why It’s OK If It’s Vague |

Interest/Domain (Business) | “Employee motivation in startups” | Broad but connected to management studies — can be narrowed later. |

Interest/Domain (Nursing) | “Preventing hospital infections” | Still vague — but easy to refine into a researchable question. |

Assignment Brief (Computer Science) | “Test a new AI algorithm” | Comes directly from the brief — will be sharpened with variables and outcomes. |

Assignment Brief (Education) | “Effectiveness of Flipped Classrooms” | Clear domain, but still wide — needs narrowing (grade level, context, timeframe). |

Step 2 — Do Some Preliminary Research

After you’ve chosen a broad topic, the next step is to do preliminary research. This is like scouting the ground before you decide exactly where to build your project. The aim is not to dive deep yet, but to map what’s out there.

You don’t need to read every article in detail. Instead, skim:

- A few recent journal papers

- Credible websites or policy reports

- Textbook chapters covering your area

- UK-based sources such as government publications (e.g., Department for Education, NHS Digital, Office for National Statistics) or sector-specific reports (e.g., CBI for business, Ofsted reports for education)

The goal here is not to find the answer, but to spot the possibilities.

Ask yourself:

- What questions have already been answered?

- What are researchers still debating?

- Where do I see gaps or controversies?

Example

Suppose your broad topic is “online learning.”

When you do some quick scanning, you might find:

- Academic performance: Many studies measure online learning’s effect on exam scores and grades.

- Engagement and motivation: Some papers look at whether students feel motivated or stay engaged in online classes.

- Mental health and well-being: A few studies mention stress, isolation, or anxiety linked to online learning, but less often.

- Access and equity: Reports highlight digital divides — rural vs urban students, or differences based on socio-economic status.

- Skill development: Some research explores critical thinking, collaboration, or problem-solving in online settings.

At this point, you don’t need to choose yet. But noticing that performance has been widely studied while mental health or equity issues are less explored can give you multiple possible seeds for a research question.

UK Student Tip

When doing preliminary research, check resources like the British Education Index, NHS Evidence, or the UK Data Service. These are trusted sources often recommended by UK supervisors and can help you ground your dissertation in reliable data.

Tip

Don’t drown in details. At this stage, you’re not solving the problem; you’re just mapping the landscape. Focus on the big-picture issues authors highlight in the introduction or conclusion sections of papers.

By the end of preliminary research, you should have a shortlist of promising directions. To explore these systematically, move on to the Literature Review stage.

Step 3 — Develop and Structure Your Research Question

Once you’ve done some preliminary research, the next step is to narrow your topic into something manageable. At UK universities, this stage is especially important because supervisors and examiners expect your question to be specific, researchable, and realistic within the word count and timeframe of your dissertation.

There are two simple ways to structure your question:

Method A: Manual “Narrow & Structure” — start broad, then narrow by choosing a specific outcome, population, factor, context, and timeframe; then assemble those parts into one clear sentence.

Method B: Framework Shortcut — plug your topic into a ready-made pattern (e.g., PICO / PICOC / SPIDER) to ensure you’ve covered Population, Factor, Outcome, and optional Comparison/Context. (We’ll do this right after the table.)

We’ll start with Method A, which is based on how many UK supervisors guide students during proposal discussions.

Method A — Manual “Narrow & Structure”

This method is like peeling an onion: you start broad, then strip away layers until you’re left with a clear, focused question. Follow these 5 narrowing steps:

Step 1: Start Broad

Begin with a large area of interest.

- Example: “The effect of social media on children’s mental health.”

- Too vague: “social media” = many platforms, “mental health” = many outcomes.

Step 2: Choose One Outcome

Pick just one aspect or sub-area.

Example: Instead of all of “mental health,” focus on self-esteem.

Now it becomes: “The effect of social media on children’s self-esteem.

Step 3: Define Your Population

Make the group precise.

Example: Instead of all “children,” pick 8–12-year-olds.

Now: “The effect of social media on the self-esteem of 8–12-year-old children.”

Step 4: Pin Down the Factor or Variable

Specify what exactly you’re testing/observing.

Example: Instead of all “social media,” pick Instagram.

Now: “The effect of Instagram use on the self-esteem of 8–12-year-old children.”

Step 5: Add Context and/or Timeframe

Situate your study in a place or period.

Example: Context = urban schools, Time = last five years.

Final Draft: “What is the effect of frequent Instagram use on the self-esteem of 8–12-year-old children in urban schools according to recent research?”

Notice the progression: each step cuts away vagueness until the question is specific, measurable, and feasible.

UK Student Tip

When you reach this stage, always cross-check your draft question against your university’s dissertation handbook. Many UK institutions (e.g., Sheffield, Manchester, Hertfordshire) require you to justify not just what your question is, but also why it is feasible, ethical, and relevant within the UK context.

Example of Research questions 2: Walkthrough (Machine Learning Example)

- Step 1 (Broad): “Improving medical image classification.”

- Step 2 (Outcome): focus on model accuracy.

- Step 3 (Population/Data): Use public chest X-ray datasets.

- Step 4 (Factor): test data augmentation vs no augmentation.

- Step 5 (Context/Time): deep learning models; recent years.

Final Question: How do specific data augmentation techniques, compared to no augmentation, influence the AUC performance and generalizability of deep-learning models on public chest X-ray datasets, according to recent studies?

Quick Recipe Table — Narrowing in Action

Domain | Step 1: Broad Topic | Step 2: Outcome | Step 3: Population | Step 4: Factor/Variable | Step 5: Context/Timeframe | Final Research Question |

Social Media & Children | Social media and children’s mental health | Focus on self-esteem & anxiety | Children aged 8–12 | Instagram use | Urban schools, the last 5 years | How do parental strategies and Instagram use moderate appearance comparison, self-esteem, and anxiety in 8–12-year-olds? |

ML / AI | Improving medical image classification | Model accuracy (AUC) | Public chest X-ray datasets | Data augmentation (vs. none) | Deep learning models, recent studies | How do data augmentation techniques affect deep-learning model performance and generalizability on chest X-rays? |

Nursing / Health | Stress in nursing students | Exam stress levels | Undergraduate nursing students | 15-minute daily mindfulness routine (vs. none) | During exam weeks, current semester | What is the impact of a daily 15-minute mindfulness routine on exam stress levels in undergraduate nursing students during exam weeks, compared to no intervention?. |

Education | Teaching methods and learning outcomes | Critical thinking | Grade 10 students | Flipped classroom (vs. lecture) | Urban public schools, exam prep | What are the influences of flipped versus lecture-based classrooms on the critical thinking development of Grade 10 urban students during exam preparation? |

Business / Management | Leadership in companies | Employee retention / turnover | Employees in small IT startups | Transformational leadership (vs. transactional) | Indian IT startups, current year | How does the transformational leadership style influence employee turnover compared with the transactional leadership style? |

Environment / Sustainability | Transport policies and air quality | Air-pollution levels | Residents of Delhi | Introduction of electric buses | Since 2020 | What changes in spatial and temporal air pollution patterns have occurred in Delhi since 2020, correlated with the rollout of electric buses? |

Method B — Framework Shortcut

Sometimes the step-by-step narrowing feels slow or overwhelming. That’s where frameworks come in — they’re like templates that help you structure a research question quickly without missing any critical pieces.

Here are the most commonly used ones in universities:

PICO — Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

This framework is commonly used in health sciences and nursing research. It helps you organise your question around four core elements:

Population → Who are you focusing on? For instance, this could be nursing students, patients, or a specific age group.

Intervention (or factor) → What is being introduced or studied? This might be a treatment, a routine, or a particular method.

Comparison → What is the baseline or alternative against which you measure the intervention? For example, comparing a new routine to no routine at all.

Outcome → What result do you want to observe? This might be stress reduction, improved recovery times, or exam performance.

Example: To what extent has hybrid working (Intervention) influenced employee retention (Outcome) among IT firms (Population) compared with traditional office-based work (Comparison) in the post-pandemic UK business environment (Context)?”

PICOT — Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Time

PICOT builds on PICO by adding Time as a fifth element. This is especially useful in studies where the effect of an intervention depends on the time period being observed.

Population → The group under study, such as patients in a hospital ward or students in a course.

Intervention → The specific change or method applied.

Comparison → What you measure it against.

Outcome → The measurable effect you want to capture.

Time → The duration or time frame, such as “over six months” or “during exam season.”

Example: How does the introduction of electronic triage systems (Intervention) influence patient waiting times (Outcome) in UK emergency departments (Population) compared with paper-based triage (Comparison) over a three-year period (Time)?”

SPIDER — Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type

SPIDER is particularly suited for qualitative and exploratory studies, which are common in education and social sciences. It shifts focus from interventions to lived experiences and perceptions.

Sample → The group under study (e.g., teachers, parents, employees).

Phenomenon of Interest → What experience or issue are you examining? For instance, the shift to blended learning or workplace stress.

Design → How you will collect data (e.g., interviews, focus groups).

Evaluation → What aspect are you assessing, such as satisfaction, effectiveness, or perceptions?

Research type → The overall approach, usually qualitative, mixed methods, or case study.

Example: How do secondary school teachers (Sample) experience the shift to blended learning (Phenomenon of Interest) when interviewed through focus groups (Design), and how do they evaluate its effect on teaching quality (Evaluation) within a qualitative case study (Research type)?

Quick Tip: Run a FINER Check on Your Draft

Once you’ve built a draft question (manual or framework), pause and test it with the FINER checklist.

A strong research question should be:

F — Feasible: Can you realistically study this with your time and data?

I — Interesting: Will the answer matter to you and your field?

N — Novel: Does it add something new (even a fresh angle on old data)?

E — Ethical: Can you study it without harming participants?

R — Relevant: Does it connect to real issues in your discipline or society?

Let's take our early example, which we framed: How does daily Instagram use affect anxiety scores in adolescents aged 13–18?

Feasible? Yes → measurable with surveys.

Interesting? Yes → hot topic in education & psychology.

Novel? Yes → focuses on a single platform & outcome.

Ethical? Yes → surveys are non-invasive.

Relevant? Yes → directly linked to adolescent wellbeing.

If your question doesn’t pass FINER, go back a step and tighten it.

Conclusion

A strong dissertation begins with a strong research question. Throughout this guide, we explored how to move from vague ideas to clear, focused, and feasible questions by using simple steps, proven frameworks, and practical examples. Whether you choose to frame your question manually or through structured frameworks like PICO, PICOT, PICOC, or SPIDER, the key is clarity, specificity, and feasibility. And by applying tools like the FINER checklist, you can refine your draft into a question that truly stands up to academic scrutiny. Now, with this roadmap in hand, you are better equipped to craft a question that doesn’t just satisfy an assignment brief but lays the foundation for a meaningful and successful dissertation. If at any point you feel unsure, remember, AssignmentHelp4Me expert guidance is always available. We guide students through every stage of dissertation writing—from building a solid introduction chapter to structuring the literature review, shaping the methodology, analyzing data, and finalizing the conclusion with precision.

Now that you’re familiar with research questions, take a look at practical research question examples and expert insights in qualitative research methods.